Carningli

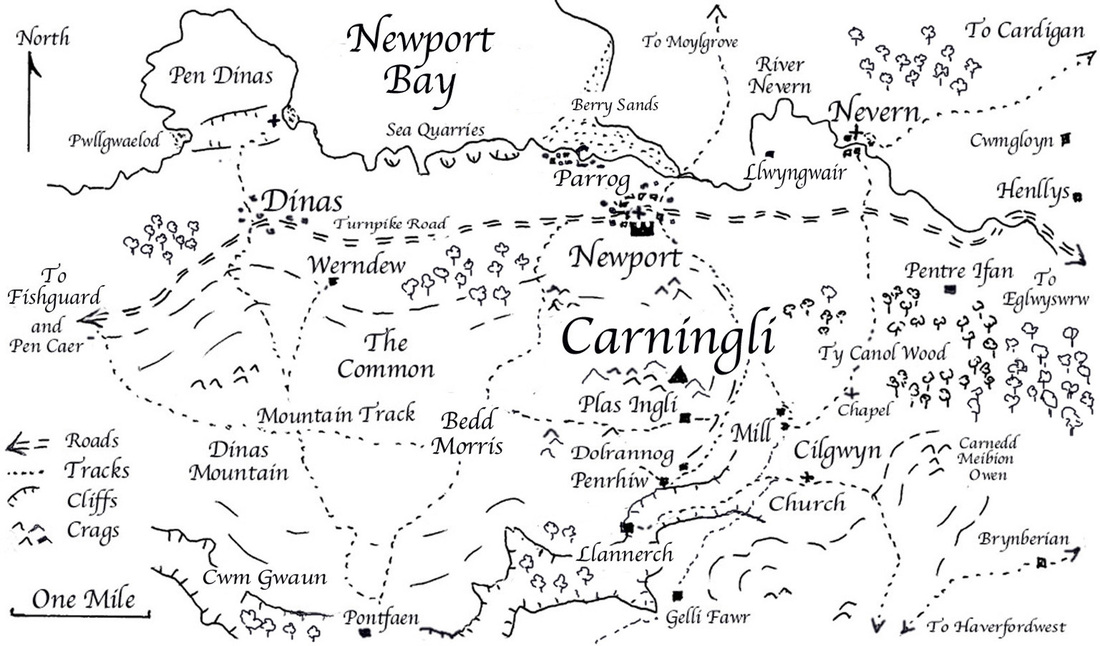

The little mountain of Carningli dominates the landscape around Newport and Cilgwyn, and although it is only 347m ( 1,138 feet) high it is visible as a prominent feature from the north and east, and even from the south, for travellers approaching from Mynydd Preseli. From certain directions, the mountain looks like a volcanic peak -- and this is appropriate, since it is indeed an ancient volcano. But it is extremely ancient -- around 450 million years old, be be almost precise -- and its present-day profile gives us little guidance as to what it looked like when it was erupting. When the mountain was born, the area which we currently call North Pembrokeshire was part of a great ocean, the bed of which was buckled up and down and shattered by earth movements and mountain building over millions of years. There was virtually no life on land, and very little in the sea. We know that there were tens if not hundreds of volcanoes across a wide area, since dolerites and other volcanic rocks occur in virtually all of the high points of the landscape.

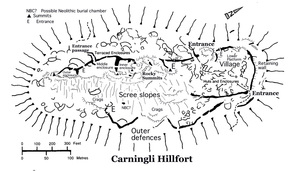

Carningli probably started to emerge from the sea as a violent volcanic island, appearing, erupting and growing just as the Icelandic island of Surtsey did in 1963. Ash and lava from the eruption must be present over a wide area beneath the present-day land surface, interbedded with old sea-floor sediments of sand, silt and clay which have now been transformed into solid rock. The only place where we can see the volcanic ash today is in the cliffs between Newport and Cwm-yr-Eglwys, in great beds of crumbly grey material which looks very different from the dark-coloured and flaky shale which the locals call “rab.” When the Carningli eruption came to an end, the volcanic island immediately started to be whittled away by wave action, wind and running water. The land surface, originally many thousands of feet above its present position, was lowered inexorably by erosion, so that what we see today is essentially the “core” of the original mountain, made largely of a very hard blue-grey rock called dolerite. Some of it is “spotted dolerite” like the famous bluestone of Carn Meini. During the Ice Age the mountain was completely covered by the ice of the massive Irish Sea Glacier, moving down from the north and north-west, possibly in several different glacial episodes. Some traces of ice erosion can still be seen on rocky slabs near the summit and on the eastern flank of the mountain. In the last glacial episode the glacier may not have over-ridden the summit, but it pressed against the northern slopes and probably into the amphitheatre of Cilgwyn, leaving the southern and eastern slopes to be afflicted by thousands of years of frost shattering. That is why the east face of Carningli is almost obliterated by a great bank of scree even today. Martha and her children loved to climb on the great jumble of boulders and craggy outcrops, and somewhere, in the middle of it all, is Martha’s cave and the crevice into which she dumped Moses Lloyd’s body. The summit of the mountain is protected in part by a splendid defensive embankment, now somewhat ruinous but still obvious to all who climb up from the north or west. In its heyday it was probably about 10 feet high, with a vertical outward face, and maybe even a timber palisade on top. When you climb up from the east (for example, from the car-park on the Dolrannog Road) the embankment is not so obvious; that is because the scree slopes provided good natural defences for the inhabitants of the mountain against marauding warriors. So the embankment never did enclose the whole of the summit. There was a fortified village here, aligned more or less SW-NE, with three segments. The builders knew all about military architecture, and in some ways it was just as sophisticated as that of the Normans who followed maybe 2,000 years later. |

Continued...

In the south-west is the outer enclosure, approached through a fine gateway passage with flanking walls from what is now the open common. Animals may have been brought into this flattish area at times of trouble. Then there is a “cross wall” with a gateway in it, which separates the outer enclosure from the “inner bailey”. This area encloses the three inhospitable craggy summits of the mountain; here there might have been some crude shelters against the rock faces, but the inhabitants would only have used it in times of great crisis. Then on the north-eastern side of the mountain (on the lee side, away from the prevailing wind) there are two natural platforms on which we can still see hut circles and small enclosures. This was the main living area, and archaeologists think there may have been about 25 houses here, providing shelter for 150 people. These houses would not have looked like the reconstructed round houses of Castell Henllys! Here it was far too exposed for such exotic structures to survive, and so we are talking about very crude shelters, partly excavated into the stony ground and roofed over with a low lattice of branches, thatch and animal skins. Possibly these “houses” were so low and primitive that it was not even possible to stand up inside them. This living area is actually encolosed by defensive walls on three sides. Altogether there are nine entrances through the main defensive embankment. Gates are always vulnerable, and this leads archaeologists to think that those who lived here were not particularly threatened by enemy tribes. On both the western and eastern sides of the mountain, outside the main defended area, there are scores of embankments, paddocks and the remains of other shelters which must have been used in the pastoral and farming economy, for keeping sheep, cattle and goats and for growing and storing human food supplies and fodder. These features are all prominent, except at the height of summer when the bracken is high. The most prominent features of all are two gigantic looped banks on the eastern side of the mountain at the foot of the scree slope. Who built the Carningli hillfort? In Martha’s day most people simply assumed that “The Ancient Druids” built almost all of the old man-made features in the landscape, some time after Noah’s Flood had obliterated everything. Now we know that the Carningli village was occupied during the Iron Age -- but we still do not know for sure whether it was a permanent settlement, or one that was simply occupied during the summer season by people who spent their winters in the sheltered woodlands of the river valleys. The site has never been properly excavated, so there are very few clues to be interpreted. There are some old records which suggest the the mountain was occupied by vagrants and travellers well into the Middle Ages and maybe even later, and at the other end of the scale it is now suggested that the earliest occupants may well have been here during the Bronze Age around 3,000 years ago or possibly even in the Neolithic, more than 4,000 years ago. So some of the stone walls around the summit may be older than the pyramids of Egypt, and the site may have been occupied (intermittently) by many different groups of people over something like 3,500 years. With such a history of settlement, perhaps we should not be surprised that the mountain has been thought of as a “sacred mountain” for a very long time. There are no burials on the summit (although there may well have been human sacrifices and executions, given that the Iron Age was a pretty brutal time), so Carningli may not have been thought of as a particularly sacred or spiritual place in pre-Christian times. But when St Brynach, our local saint, came into the district around 450 AD to convert the heathen and to found his monastery at Nevern, we learn from the old texts that he was instantly attracted to the mountain. When life at the monastery became too frantic (it was, after all, on the pilgrim route to St Davids) he used to climb up onto the summit in order to “commune with the angels.” That was one way of saying that he went to find solitude, to fast, and to spend time in contemplation and prayer. It may be that during the Age of the Saints the mountain acquired the name “Mons Angelorum”, and it was still called this in educated circles around the year 1600. The name “Carningli” is difficult to translate, but in old Welsh it may well mean “Mount of the Angels” -- and on old maps it is called Carn Yengly or Carnengli, which are probably both corruptions of Carn Engylau. So where does this aura of sanctity come from? Well, all who climb onto the summit know that is a very special place -- high enough above the surrounding countryside to be closer to heaven than everywhere else, low enough to be easily accessible to those who are reasonably fit, and not quite rocky enough to be dangerous or threatening. When you are on the mountain by yourself you can look down on the world with nothing but the whisper of the wind and the song of the skylarks in your ears, while you watch, far below, the bustle of Newport and the traffic speeding along the Fishguard - Cardigan road. Peace and quiet, only thirty minutes’ climb from the town centre. Even today, the place is sacred. In the stories, Martha taps into the sanctity of the place just as I do on every visit and just as thousands of others do. But note that in the stories Martha is the only one who looks on Carningli as her cathedral --- her children look on the place as a playground and as somewhere to have adventures, and the servants at the Plas look on it as a place which provides shelter from the northerly winds and which conversely endangers grazing animals. Martha’s “special relationship” with the mountain is important as a storytelling device -- to enhance the “sense of place” in the Saga, and also to show that Martha is a very spiritual person although she may not be “religious.” Nowadays the mountain is widely used for worship and for rituals. It is a common thing for people who love the mountain to ask that their ashes should be scattered from the summit when they die -- and their surviving relatives are very willing to oblige. I have often seen bunches of flowers, ribbons and other keepsakes or personal momentoes on the summit-- and I can only assume that people use the mountain for prayers, for those who are ill or troubled, in exactly the same way as the people of Ireland use their roadside shrines. Some people who are into witchcraft use the mountain, as do the adherents of other religions including Buddhism. |

Continued......

Then there is the shape of the mountain. It has to be female, just as the spirit of the mountain is female. When you look at Carningli from the south or south-east, it has the unmistakeable skyline profile of a woman lying on her back. To the left you see the head, with a strong forehead, and then the prominent breast and rib cage, and finally to the right the raised knees. Some people think that the reclining figure is pregnant, but that depends on your viewpoint. Perhaps the profile helps to explain the sanctity of the mountain, and author and long-distance walker Lawrence Main thinks that the summit of the mountain is on an ancient “spirit path” and is also a manifestation of the Earth Goddess. Lawrence believes that Carningli is not just a goddess but also a sleeping giant, which makes the mountain a place of great spiritual power. He calls her Rhiannon. Laurence claims to have spent over 700 nights on Carningli since 1995, sometimes in a tent and sometimes in the open. He is very attuned to the presence of angels on the mountain, and for some years he has conducted “dreaming experiments” with volunteers on the green patch adjacent to the summit, using the early Celtic tradition that the earth remembers everything and speaks through the dreamer. The theory is that those who are chosen will dream of angels when they sleep on the green patch which is the navel of the Earth Goddess. Not everybody who sleeps there does dream of angels, and not everybody finds it easy to identify with Lawrence’s ideas, but we all have our own realities, and I am more than a little intrigued that when the story of Martha Morgan came into my head in 1999 I knew that she would die on the mountain summit. So when I came to write the final chapter of Flying with Angels it was entirely natural that she should die in exactly the same position, lying on her back, at peace beneath the frosty stars. So are Martha and Rhiannon one and the same? Lawrence talks of the Earth Goddess, while others, who are not into goddesses and angels, refer to Martha as “Mother Wales.” Has the story of Martha been given to me by Rhiannon or by the spirit of the mountain? Now there’s an interesting thought......... There are many records of strange phenomena on Carningli, and these perhaps help to explain why the mountain is deemed to be sacred. Two or three of my acquaintances have observed rainbow haloes around the summit, caused (if you are inclined to scientific explanations) by thin mist around the rocks and sunlight above, projecting shadows and catching and scattering the colours of the spectrum on water droplets. TC Lethbridge called this “the broken spectre”, and Welbourne Tekh experienced it in a stunning form in 1997 when he climbed to the summit in clearing cloud, after heavy rain. I have been on the summit myself, on many occasions, when sea mist has been rolling in from the coast and the topmost crags stand like little islands above the surface of an ocean of white foam. Swirls of mist roll in slow motion through the gaps between the rocks, and the effect is eerie and very beautiful. I have described some of my own “cloud effect” experiences in the pages of the novels, and have given to Mistress Martha my own sense of surprise and wonderment. And many times every year, when high-altitude cirrus clouds are seen above the summit of the mountain, it is easy to see in them the shapes of angels’ wings. On many such occasions I have heard the comment “Ah, the angels are flying over Carningli today.” Now, from the sublime to the ridiculous. At the top of the green track that leads up the mountain from the Dolrannog Road parking area, there are two masonry pillars with a narrow gap between them. One of my friends refers to these pillars as “the gateway to Carningli” and she will not go up the mountain, or come down off it, without passing between them. Above the gateway is the craggy mountain with all its mysteries, and below it is the humdrum world of everyday life. Fair enough, but the origins of the pillare are far more prosaic. From what I can gather from the older local residents, the pillars are the most obvious relics of Carningli’s industrial revolution. They are located at the top of the “Carningli Mountain Railway” which operated for a few years between the two World Wars during a time of substantial road improvements by Pembrokeshire County Council. The hundreds of little roads around Newport and Cilgwyn were being improved and provided with asphalt surfaces, and there was a great demand for crushed roadstone. Seeing a commercial opportunity in this, five Newport men decided that Carningli bluestone would fit the bill perfectly, since it could be obtained in good quantities from the lower scree slopes of the mountain with relatively little effort. They cleared things with the Commoners, applied to the Barony of Cemais for permission to take stone from the mountain (in exchange for a royalty for every ton taken), and did a deal with PCC. They set up in business, and built a narrow-guage railway track about 500 yards long from the Cilgwyn Road up onto the mountain side. It runs almost east-west. In some places the men had to build embankments, and in others they had to excavate cuttings. They built a small crushing plant at the roadside, operated by a diesel engine. At the top of the incline they constructed two masonry pillars to support a large cable drum, the mountings for which were fixed on two large iron bolts on the top of each pillar. Another diesel engine was installed adjacent to the pillars, and this provided the power to rotate the drum and pull in the cable. They installed the railway track and bought three little railway trucks, which were connected together and then coupled to one end of the cable. When the trucks were stationed at the top of the incline they could be filled with blocks of stone carried from the quarrying area in a horse-drawn cart. Then they would be let down under the force of gravity, using a braking system on the cable drum to control the rate of descent. When they reached the bottom, they would be unloaded and the stone fed into the crushing plant. Then the upper diesel motor would be started, and the cable would be wound in again, pulling the three trucks back up to the top of the incline for a fresh load of stone. I have never seen any written records (or photographs) of this short-lived industrial enterprise, but according to legend it only lasted for a few years. Two men worked in the crushing plant and three up on the mountain. The “quarry” was maybe a hundred yards long, extending southwards along the contour from the winding gear. There are several obvious cuts into the mountain slope, but probably most of the rock which has been taken consisted of loose boulders and scree rather than solid rock. In the quarry the rock was broken up into stones about the size of footballs. Today we can still see still some piles of excavated stones here and there, but the most obvious trace of the quarrying activity is a cutting or gully which was used by the horse and cart for its journeys back and forth in delivering stone to the “loading bay”. Today all that can be seen of this little enterprise is the smooth green track of the incline, with a few metal sleepers showing through the turf, the winding-gear pillars, the overgrown quarrying area, and a little ruined hut to the north of the incline which might have been used as a shelter for the workmen. There is no trace at all of the crushing plant on the Cilgwyn Road. And what was it that brought the Industrial Revolution on Carningli to an end? It must have been a truly spectacular event. According to legend, one day around 1933 the man in the quarry who had charge of the dynamite became a little too enthusiastic, and this led to an almighty explosion which caused fragments of shattered bluestone to rain down upon the roofs of all the cottages in the cwm. Thankfully nobody was hurt, but there was such an outcry that the firm’s operating licence was revoked. The men dismantled their machinery and sold it off, leaving the mountain once again in the possession of sheep and angels. |